Our September 2022 meeting for LMCC took place on Wednesday, September 28 at 5:30pm est in the HHIVE Lab and via Zoom. We continued discussing Abigail A. Dumes’s 2020 monograph from Duke University Press, Divided Bodies: Lyme Disease, Contested Illness, and Evidence-Based Medicine.

Dumes’s 2020 monograph from Duke University Press, Divided Bodies: Lyme Disease, Contested Illness, and Evidence-Based Medicine.

At our previous meeting on September 1, we had discuss the introduction, “Lyme Disease Outside In” (pp. 1-25). At our most recent meeting, we focused more specifically on chapter 5, “Lyme Disease, Evidence-Based Medicine, and the Biopolitics of Truthmaking,” pp. 187-221. We also briefly discussed her recent article “Long COVID Holds a Mirror Up to Modern Medicine” in The New York Times and reprinted in The Salt Lake Tribune in March 2022.

If you missed the meeting, you can still access the text on the Readings page of this site.

Although we usually try to record our meetings, due to some technical issues, we were unable to record this particular meeting. However, for recordings of some of our past meetings, click here.

Our next meeting will take place on Wednesday, October 26 at 5:30pm in the HHIVE Lab, also called Gaskin Library, Greenlaw Hall Room 524. If you can’t attend in person, you can attend in real-time via our usual Zoom link. We will send out an announcement soon with more information for that meeting.

A few reminders and announcements:

- LMCC now has a Twitter and Instagram account. Be sure to follow us there to show your support and receive regular updates!

- Scroll to the bottom of this site and “Subscribe by Email” so you get notified each time we post an announcement to the site!

- If you want to get more involved with LMCC, please send us other resources we should post to the site or suggestions for improvements, additions, future readings, etc. We’d love to hear your ideas and input! (See our email addresses on the Home page of this site.)

- Also, please feel free to spread the word about LMCC to other interested graduate or professional students at UNC.

Dumes, Abigail A. “Lyme Disease, Evidence-Based Medicine, and the Biopolitics of Truthmaking.” Divided Bodies: Lyme Disease, Contested Illness, and Evidence-Based Medicine. Duke UP, 2020, pp. 187-221. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478007395.

Some key passages:

(See also notes and key passages from our Sept. 1 discussion of the introduction to Dumes’s monograph.)

“In its controversy over how diagnosis and treatment should be standardized and regulated across time and space, the case of Lyme disease also highlights the biopolitical dimension of the relationship between contested illness and evidence-based medicine” (Dumes 187).

“In this chapter, I explore the relationship between evidence-based medicine, the standards it creates, and the controversy over whose truths about Lyme disease get to count. Drawing from interviews and conversations with Lyme physicians and scientists, I argue that, in addition to standardizing medical practice, evidence-based medicine has the unintended consequence of amplifying differences in practice and opinion by providing a platform of legitimacy on which all individuals—from patients and physicians to scientists and politicians—can make claims to medical truth. Finally, I suggest that evidence-based medicine can be more fully understood as a technology of biopower that regulates bodies in the pursuit of more ‘effective and efficient’ medicine, as well as a form of ‘biolegitimacy’ that, in its emphasis on the evidentiary legitimacy of bodily signs, simultaneously produces a categorical division between the ‘right way to be sick’ (medically explainable) and the ‘wrong way to be sick’ (medically unexplainable), which are correspondingly perceived to be worthy and unworthy of biomedical attention” (Dumes 188).

“Described as both a ‘paradigm shift’ and a ‘social movement,’ evidence-based medicine is an approach to standardizing clinical practice that gained momentum in the late 1980s and is often defined as ‘the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’” (Timmermans and Berg 2003, 3, cited in Dumes 189).

“Like any locus of power, evidence-based medicine is simultaneously many things. It is a set of practices; a discourse; an assemblage of individuals, technologies, and institutions; and a term that is simply understood to describe the experience of contemporary biomedicine itself” (Dumes 189).

“…there have been as many practitioners and scholars who have criticized evidence-based medicine for unduly regulating medical decision-making on an individual basis, obscuring ‘subjectivity,’ and reinforcing ‘monopolies of knowledge’” (Dumes 191).

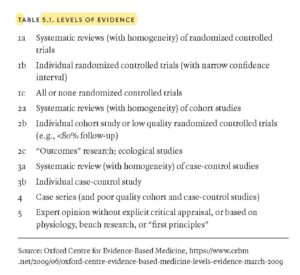

“Through praise, discontent, and indifference, evidence-based medicine, in its entirety, has come to encompass several key components: a hierarchy of scientific evidence, clinical guidelines, and evidence-based practice centers” (Dumes 191).

“…all scales of evidence are organized according to the probability of bias. That is, systemic reviews of randomized controlled trials are understood to be the strongest evidence because they are understood to contain the least bias, while expert opinion is understood to be the weakest evidence because it is understood to contain the most bias” (Dumes 191).

“Established in 1997 by the AHRQ [Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality], evidence-based practice centers are located at research hospitals, medical centers, and other research institutions, and their purpose is to conduct ‘evidence reports’ for the Effective Health Care Program, which provides funding to individuals and organizations to ‘hel[p] consumers, health care professionals, and policymakers make informed and evidence-based health care decisions’” (Dumes 193).

“Perhaps more than any other feature of evidence-based medicine, evidence-based practice centers highlight the extent to which evidence-based medicine has become an important part of the biopolitical management of health in the United States” (Dumes 193).

“Drawing on evidence-based medicine’s rich lexicon, mainstream Lyme physicians are quick to emphasize that all evidence is not equal, and that ‘strength’ of evidence matters…. Lyme-literate physicians and Lyme patients are acutely aware that mainstream physicians and scientists perceive their evidence to be ‘weaker’ evidence” (Dumes 194).

“The catch, however, is that each side interprets the evidence from those studies differently. Perhaps not surprisingly, while mainstream physicians argue that the data from those studies show that long-term antibiotics have no benefit, Lyme-literate physicians argue that the data from those studies demonstrate measurable improvement in fatigue” (Dumes 195).

“…although intended to resolve disputes, evidence-based medicine provides a means by which each of Lyme’s two camps reinforces its respective standard of care through different ‘styles of scientific practice’ and, in so doing, often produces the very ‘uncertainty’ that evidence-based medicine attempts to ‘settle’” (Dumes 195).

“The phenomenon of differently interpreting data to reinforce a preexisting opinion is not unique to Lyme disease—it is a hallmark feature of evidence-based medicine. Across a wide range of topics and specialties, evidence-based medicine inadvertently produces and legitimizes differences in medical practice and opinion by providing a language of legitimacy through which all individuals can make claims to medical truth” (Dumes 195).

“As one of evidence-based medicine’s most heavily relied-on tools, meta-analyses aggregate and synthesize all available evidence on a particular topic to arrive at one encompassing truth. Although the goal of performing a meta-analysis is to distill similarity from difference and achieve consensus, the end result is that meta-analyses also reinforce preexisting differences by providing a platform on which anyone with access to evidence-based information can make a claim to truth” (Dumes 196).

“Where mainstream concerns about evidence-based medicine tend to be related to diminished clinical autonomy, concerns among Lyme-literate physicians tend to be related to how evidence-based medicine—primarily in the form of guidelines—is wielded and leveraged as a form of power” (Dumes 196).

“Lyme-literate physicians also expressed concerns about the variability with which evidence can be interpreted and how, in these cases, the interpretation held by the more powerful entity is the one that is perceived to be more legitimate” (Dumes 197).

“Across the board, however, Lyme-literate physicians’ most common criticism of evidence-based medicine guidelines is that, despite being promulgated as recommendations supported by the highest level of evidence, the majority of recommendations are supported only by ‘expert opinion,’ the lowest-ranking form of evidence in evidence-based medicine” (Dumes 199).

“For mainstream physicians, Lyme-literate physicians’ medical society and their guidelines constitute a well-crafted marketing stunt that has successfully deceived many patients and politicians. For Lyme-literate physicians, however, their approach to diagnosing and treating Lyme disease constitutes a more sophisticated standard of care than that of the IDSA [Infectious Diseases Society of America], and, for them, evidence-based medicine provides a path toward vindication and a means to reducing what is perceived to be the disparity of power between themselves and the mainstream” (Dumes 201).

“The IDSA first published its diagnosis and treatment guidelines on Lyme disease in 2000. Six years later, in 2006, the guidelines were reviewed and updated to include new findings. Soon after they were published, Richard Blumenthal, the former Connecticut attorney general and current Connecticut senator, launched an antitrust investigation into the IDSA’s guideline-making process by issuing the IDSA a subpoena. It was the first investigation of its kind. Influenced by the appeals of three prominent Lyme advocacy organizations, this investigation was premised on two major claims. The first was that the guideline panelists had significant undisclosed financial conflicts of interest. The second, which followed from the first, was that, in violating antitrust laws, the guidelines ‘restrain[ed] doctor and patient choices for the treatment of the disease’ and ‘prevent[ed] physicians’ clinical judgment’” (Asher 2011, 124, cited in Dumes 202).

“In its account [following a settlement that ended the investigation], the IDSA emphasized that the guidelines remained in effect and that its members had agreed to a voluntary review of the guidelines process, not because they were concerned that the guidelines were not ‘the best advice that medicine currently has to offer,’ but to put to rest the ‘unfounded’ assertion that the IDSA had ‘ignored divergent opinion.’ It also denied the validity of the investigation’s findings, all of which centered on conflicts of interest and the exclusion of divergent opinion” (Dumes 203).

“Years later, the Connecticut House of Representatives, through efforts not related to those of the attorney general, passed Connecticut House Bill No. 6200, named by Lyme advocates as the Lyme Doctor Protection Bill. This bill, which went into effect on July 1, 2009, effectively sanctioned the use of long-term antibiotics in the treatment of Lyme disease in Connecticut; it also protected physicians from being ‘subject to disciplinary action by the Connecticut Medical Examining Board solely on the basis of prescribing, administering, or dispensing long-term antibiotic therapy.’ Together, Public Act 99-284 and House Bill No. 6200 provide more legal accommodations for the extended treatment of Lyme disease in Connecticut than exist in most states. Nevertheless, a Lyme-literate physician with whom I spoke, who does not practice in Connecticut, observed that despite Connecticut’s legal safety net, relatively few physicians actually treat with extended antibiotics because of ‘peer pressure’” (Dumes 206).

“In the case of clinical guidelines and similar concerns about how guidelines could be used to reinforce industrial interests, some physicians and scientists have been vocal in calling attention to the risks and realities of conflicted interests in guideline-making and their implications for patient care…. They also recommend that significant ‘benefit’ from any particular company should disqualify that individual from being able to participate in guideline-making related to that company’s particular product” (Dumes 211).

“For many Lyme patients, advocates, and Lyme-literate physicians, the IDSA guidelines are perceived to function as a ‘sword’ not only by disciplining Lyme-literate physicians like Dr. Albert who do not follow its standard of care but also by providing the basis on which insurance companies can deny coverage for extended antibiotic treatment and, in doing so, reduce costs” (Dumes 213).

“For many of the Lyme-literate physicians and patients I spoke with, the IDSA’s perceived ties to the insurance industry appeared to be the most compelling explanation for why it refused to recognize chronic Lyme disease” (Dumes 213).

“Shared conflicts of interest aside, when it comes to whose ideas about Lyme disease matter, the primary difference between the two standards of care, their guidelines, and their associated medical societies is unequal ‘capital.’… Even though both standards of care have their own set of guidelines, which is a critical component of evidence-based legitimacy, the guidelines are not broadly perceived to have the same authority and legitimacy, or to be equally ‘true’” (Dumes 214).

“In this book’s introduction, I describe the mainstream standard of care as an example of a ‘dominant epidemiological paradigm,’ a paradigm created by a range of individuals who draw on institutional knowledge to set the terms of how a disease is understood (P. Brown et al. 2004). In thinking about Lyme’s standards of care in the context of symbolic capital, legitimacy, and attendant relations of power, they can also be understood as examples of what Didier Fassin and Robert Aronowitz have both described as ‘orthodox’ versus ‘heterodox’ entities, entities that, in relation to each other, are characterized by unequal relations of epistemic authority” (Dumes 215).

“…although financial conflicts of interest and industrial ties tend to be the most frequently cited reasons for the persistence and intractability of Lyme’s controversy, the competing claims to biological legitimacy and epistemo-legitimacy that characterize Lyme’s divided bodies may stem more from differences over what kind of evidence matters and how that evidence gets produced than from the overt conflict and conspiratorial collusions that lie at Lyme’s surface” (Dumes 216).

“Like all contested illnesses, Lyme disease is political because contestations over how to diagnose and treat it entail politician involvement, medical board hearings, legislative hearings, class action lawsuits, patient advocacy, and, not least of all, claims of bias and conflicts of interest. But because the controversy over Lyme disease is equally about how evidence-based medicine is used to regulate bodies and produce medical truths about those bodies, it also highlights how evidence-based medicine operates as a potent form of biopower and biolegitimacy” (Dumes 217).

“…evidence-based medicine is more than just a tool to guide clinical decision-making. As demonstrated by the examples of its institutionalization in agencies and initiatives within the US government, evidence-based medicine is also a means by which state and nonstate authorities can more ‘efficiently and effectively’ manage the health of their population. However, I also suggest that this entails not only an investment in ‘making live’ that legitimizes ‘life itself’ but also an attendant hierarchization of bodily conditions, some of which are deemed to matter more, and some of which are deemed to matter less” (Dumes 217).

“Indeed, evidence-based medicine’s power is located not in unilateral control and dominance but in its broad and democratic appeal, in the perception that it is a ‘good thing,’ and, as anthropologist Helen Lambert observes, in its ‘encompassing character’ and ‘inherent malleability’ (2009, 18). It is these features that allow evidence-based medicine to be enacted across the boundary between laboratory and life and to be individually internalized and repurposed as a foundation for competing claims to biological and epistemic legitimacy” (Dumes 218).

“Beyond biopolitics and its regulatory features, however, and within a diagnostic framework that emphasizes the importance of signs over symptoms, an equally consequential concern for the Lyme patients I spent time with was evidence-based medicine’s ‘politics of life,’ that is, the biological hierarchization of—and categorical distinction between—bodily conditions that biomedically matter and those that do not. Like the ‘delegitimation’ that patients with chronic fatigue syndrome experience (Ware 1992) or the ‘abjection’ of patients with multiple chemical sensitivity (M. Murphy 2006), chronic Lyme patients, in company with all individuals with contested illnesses whose biological basis is in dispute, suffer the misfortune of being sick in the wrong way” (Dumes 221).

“…the lived political implications of evidence-based medicine are as much about how bodies are differently legitimized and treated as they are about the regulation of those bodies” (Dumes 221).

“Prior to the 1980s in the United States, medical decision-making was generally understood to be the prerogative of individual physicians. After the institutionalization of evidence-based medicine in the late 1980s and early 1990s, medical decision-making became the object of standardization. As the case of Lyme disease reveals, one of the unintended consequences of evidence-based medicine is that, in addition to achieving medical consensus, it also reinforces differences in medical practice and opinion by providing a platform on which a range of individuals can make claims to medical truth. That evidence-based medicine is enacted, internalized, and repurposed by individuals inside and outside the medical arena underscores its biopolitical and biolegitimizing nature and the key to its power, for it is in its ecumenical appeal and ‘encompassing character’ that evidence-based medicine both regulates and differentially legitimizes biological bodies (Lambert 2009, 18, cited in Dumes 221).