Our April 2022 meeting for LMCC took place on Thursday, April 28 at 5:30pm est via Zoom. We continued discussing Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb’s 2021  monograph from the University of Chicago Press, Epidemic Empire: Colonialism, Contagion, and Terror 1817-2020.

monograph from the University of Chicago Press, Epidemic Empire: Colonialism, Contagion, and Terror 1817-2020.

In March we had discussed the preface and introduction to the book. In April, we focused more specifically on chapter 3: “Circulatory Logic,” pp. 83-125.

If you missed the meeting, you can still access the text on the Readings page of this site.

Although we usually try to record our virtual meetings, due to some technical issues, we were unable to record this particular meeting. However, for recordings of our other past virtual meetings, click here.

This was our final regular meeting of the semester. If you’re interested in summer meetings, please let us know. Otherwise, be sure to stay in touch and look out for our announcements later this summer as we plan to resume our regular monthly meetings this fall!

A few other quick reminders and announcements:

- LMCC now has a Twitter and Instagram account. Be sure to follow us there to show your support and receive regular updates!

- Scroll to the bottom of this site and “Subscribe by Email” so you get notified each time we post an announcement to the site! (Or contact us directly to ensure that you are on our email list.)

- If you want to get more involved with LMCC, please send us other resources we should post to the site or suggestions for improvements, additions, future readings, etc. We’d love to hear your ideas and input! (See our email addresses on the Home page of this site.)

- Also, please feel free to spread the word about LMCC to other interested graduate or professional students at UNC, especially students who will be new to the UNC community this fall!

Raza Kolb, Anjuli Fatima. “Circulatory Logic.” Epidemic Empire: Colonialism, Contagion, and Terror 1817-2020. U of Chicago P, 2021, pp. 83-125. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/lib/unc/detail.action?docID=6434649.

Some key passages:

(See also notes and key passages from our March discussion of the preface and introduction to Raza Kolb’s monograph.)

In her introduction, Raza Kolb’s comments on Ch. 3: “Part 1, ‘The Disease Poetics of Empire,’ is grounded in the nineteenth-century British colonial sphere…. Part 1’s final chapter, ‘Circulatory Logic,’ revisits Dracula and its relationship to Stoker’s minor works, then-contemporary science, the fear of a dissolving empire in Britain, and the politics of migration and global liquidity at the turn of the last century. I argue that the novel is a work of both epidemic and colonial literature, and one that enjoyed an extensive second life in the early years of the global War on Terror, including a veritable culture industry of vampire fiction in television, literature, and film” (Raza Kolb 22-23).

“There’s the retroactive association of the stranger with the mysterious and the monstrous, the moral coding of darkness in skin, dress, and nocturnal habits, the neighbors’ fears about the mutability of identity and susceptibility to conversion. This chapter argues that the ease of this reference—Muslim, vampire, terrorist—like other casual articulations of millennial Islamophobia, obscures the complex literary and discursive history of the association, as well as the extent to which fiction and fantastic narratives preserve the social, racial, and ethnic categories of colonialism that continue to shape global discourse” (Raza Kolb 83).

“In addition to contagion, other fears like rebellion, miscegenation, degeneracy, and dissipation were enormously important drivers of nineteenth-century culture and science. Deriving their figures, language, and generic maneuvers from forms like travelogues, imperial Gothic, Orientalism, and reformist realism, colonial efforts to textualize the bodily problems of empire strongly inflected popular works of nineteenth-century British fiction, especially those that imagined the world beyond Western Europe. These works, even as they traded in the affective coin of the terrors of rebellion and disease in the baleful East, were imprinted with a managerial and scientific rationalism that south to diminish exotic threats to the imperial body politic by rendering them legible, surveyable, and comprehensible” (Raza Kolb 85).

“By far the most enduring and popular novel in this archive [colonial Gothic writing] is Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a text so capacious in its allegorical accommodations that it has been read as incorporating nearly every threat and monster of its own time and place—including those I have been tracking in this book, like global epidemic, the shadow of the Ottoman Empire, the Mutiny in India, and the famine in Ireland—as well as carrying them forward into the present where they mingle with our own in what is now a well-documented millennial vampire surge in popular culture” (Raza Kolb 85-86).

“…we can locate Dracula in an important archive of colonial writing that sets the ‘science’ of monsters on its infinite course and advances a reading practice that borrows from the surveillance apparatus and epidemic narrative strategies of colonial disease literature” (Raza Kolb 86).

“The first sections of this chapter identify the insistence and importance of Dracula in the Islamophobic atmosphere of US at the beginning of the War on Terror, and reveal in Stoker’s textual forebears and his own archive a persistent fixation with the shifting borders or the Orient and the incursion of its materials—germs, dirt, people, blood—into imperial metropolitan space. The latter sections move away from the novel’s many specific allegorical systems to examine its staging of material circulation in, across, and at the borders of the East. Circular, mobile, self-reproducing, liquid: Dracula’s circulatory logic undoes the linear and center-margin geometries of trade, migration, and influence that structure empire. In so doing, Dracula also calls for a new kind of materialist reading attended to the movement of immunities alongside that of commodities…. The chapter concludes Part 1 of the book by showing how the legacies of the post-Mutiny decades in the British Empire establish new epistemological and military norms for twentieth- and twenty-first century colonialisms” (Raza Kolb 86).

“…villains, abnormals, and Orientalist monsters operate not only within a Western discourse of terrorism, but also describe the legacies of militarism left behind by colonialism and revived in neocolonial occupation and the soft annexation of sovereign states by debt structures, contingent aid, and multistate security operations” (Raza Kolb 88).

“…the novel’s [Dracula] textual history intersects with both colonial-era fears of the Eastern other and, more importantly, those that mark our present moment, upholding the novel’s popularity and relevance in a study of the afterlives of imperial-era monsters” (Raza Kolb 92).

“Dracula, in both theme and form, registers the terror of the circulatory logic of empire, and concentrates this terror in the circulation of disease. For this reason, and because its villain stalks the very streets of the metropole, Dracula is the monstrous text that most menacingly embodies—and, in its investigative plot and synoptic form, also theorizes—its own late-colonial moment, and points most clearly toward the monstrous metaphors that define our own. Stoker’s inflection of the colonial Gothic is preoccupied, as major readings of the novel have noted, with technologies of capital, bureaucracy, and science” (Raza Kolb 96).

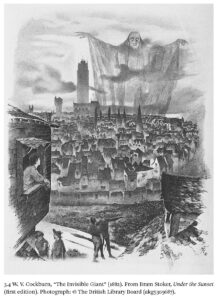

“If the short story [Stoker’s “The Invisible Giant”] is built on a straightforward symbolic economy that associates threat with disease, and proposes ‘innocence and devotion’ as its best medicaments, Dracula works by degrees of greater subtlety that correspond to the novel’s more complex representations of antipathy, where seduction joins with revulsion, and infection is a matter of intimate precision rather than a blow that fells an entire city” (Raza Kolb 101).

“Dracula shows us that waters and bloods, like histories and networks, do not sleep. They are transmitted, they live on and replicate. Each can become, under the right circumstances, the sleepless enemy itself: the night stalker, the invisible killer. In place of the center-margin geometry that shapes so much Stoker criticism, I want to suggest that the circulation of matter, material, and media is the dominant logical system in Dracula precisely because it is the dominant logical system of late empire” (Raza Kolb 102).

“Like the germ and the mutineer, Stoker’s vampire embodies the dangers and confabulation of that which falls outside imperial dialectics and monodirectional development narratives: he is both settler and migrant, mobility and shifting countenance, free-floating allegiance and thwarted recognition. The vampire’s contagious dissemination from Transylvania—his one body, his many bloods—indexes the threat of such an unaccustomed enemy, one who can move lines of engagement at will, can take many shapes simultaneously, can slip into urban space undetected, hide in plain sight, kills its victim from within” (Raza Kolb 102).

“Dracula both is, and is about, metaphor as transfer point, co-touching as contagion” (Raza Kolb 102).

“If the material successes of the British Empire can be attributed to the ever-greater mobility of commodities and the removal of all barriers, physical and legal, in their unimpeded circulation, then Dracula‘s horror strikes at the heart of this order while also revealing the horrors of an unfettered liberalism through literalizing metaphors of material transfer” (Raza Kolb 102).

“The novel’s most evident register of play with fugitive metaphor is the vampire’s shapeshifting, which untethers metaphor from a stable portrait, and disrupts a notion of the one-to-one correspondence between literary image and that which is figured” (Raza Kolb 103).

“I would suggest instead that the novel’s interest in medium, mediation, figuration, and transfiguration point up the extent to which the movement of colonial goods is always already an undoing of the center-periphery model of colonial dialectics. Rather than expressing an anxiety that the colonized will soon flood into the metropole, in other words, Dracula unfolds in the queasy knowledge that England, both England proper and its Empire, is from the very moment of its inception lousy with the pathogenic ‘goods’ of foreign lands Stoker’s vampire condenses this knowledge into a horror story on a legible scale” (Raza Kolb 106).

“As the vampire begins to fade from view—he is ultimately a poor subject for deep narration, motiveless and overdetermined by too many myths, incoherent in his many affiliations, collapsible in form and nearly inapparent—it becomes clear that the novel has no determinate or singular villain. Its horror, instead, is in the proliferative material of contagion. As it navigates towards its conclusion, Dracula‘s focus shifts from person to media, raising questions of hospitality, domain, and lair” (Raza Kolb 107).

“The horror of invisible permeability and rampant, untraceable dissemination haunts every register of disease literature, particularly in the cholera age, when the porousness of national boundaries end riverways seemed to amplify the fatally absorptive capacities of lung capillaries and bed linens” (Raza Kolb 108).

“In this section, I show how Stoker’s approach in compiling this dossier is shaped by colonial narrative form as a fundamentally remedial undertaking that invariably sought to expose if not fixed perceived pathologies in colonized subjects and spaces through meticulous recording—a feature of what historian of early colonial India Bhavani Raman has called the Raj practice of ‘bureau rule’” (Raza Kolb 112).

“Dracula not only thematizes the ontological crisis of late colonialism through its figures of liquidity, its circulatory logic, and its map of communicable disease, it also performs colonial epistemology by plotting collation and interpretation as self-sustaining activities of empire” (Raza Kolb 113).

“If at some point the novel inspired anxiety about who or what the horror of the monster was, it certainly cannot now. Narrative force and mystery emerge instead from the gaps in memory and understanding, the spaces between the texts and the memos in the dossier, and from the almost total absence of the vampire in the novel that bears his name” (Raza Kolb 115).

“Rather than simply calling Dracula a horror novel as well as a written account of our bureaucratization, I want to insist that the novel’s semi-archival form shows us how—in the colonial scene—the two are mutually constitutive, how horror becomes a fundamental aspect, a framework of imperial bureaucracy. Stokers’ textualizing project, similar to those Cohn describes, neutralizes the Eastern foreigner through description and encyclopedism even as it trades in and advances xenophobic tropes of Gothic horror. In so doing, Dracula’s investigations set a literary precedent in the nineteenth-century effort to square older forms of terror with epidemicity as an epistemological problem, a reading practice, and as a set of specific bodily and social systems brought about by the everyday practices of empire” (Raza Kolb 116).

“…Dracula explodes what Michel Foucault understood to be the nineteenth century’s signal experiments with individual bodies, which fail in every case to stand as accurate indices of the social whole, in favor of a multiple, metonymic representation of social simultaneity as the proper figure of a circulatory empire—biopolitics in advance of its theorization” (Raza Kolb 120-121).

“It is possible without abandoning these insights to follow Dracula‘s formal features as they lead us away from isolated social symptoms and toward an understanding of the novel’s allegorical elasticity through the circulatory logic that links its investigations of both mediation (textual, financial, extrasensory) and contagion (sexual, narrative, psychological). In other words, Dracula’s poly-allegorical features stage the hyperbolic fluidity and untrammeled circulation of goods, bodies, and ideas along the shifting borders of the Orient and the British empire” (Raza Kolb 121-122).

“If the pathologization of the twenty-first-century Islamist terrorist draws on the historical and narrative traditions of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century monsters, we can see not just how the fantastic morphology of the Gothic monster serves as a projection screen for the full battery of Victorian social anxieties, but also that the terror of the colonial other, the bodily risks entailed in managing a liberal empire, was already embedded in the enormous threat of infectious disease and the narratives and figures that represented them” (Raza Kolb 122).

“Dracula‘s particular geography of East-West conflict, and Stoker’s conscription of a biopolitics avant la lettre and the imperial science of epidemiology in the telling of his vampire tale place his normal firmly within a canon of colonial narratives that have profoundly shaped the easy association of Islam, violence, and epidemic in the twenty-first century. Stoker reinvents the vampire, and invents its undoing through forms of knowledge necessitated and upheld by the colonial encounter and global trade” (Raza Kolb 122-123).

“The Manichean cast of the Islam-versus-the-West binarism that has only strengthened its hold in the last two decades makes it clear that the borders of the welfare state are mere heuristics assigned to the long-standing extramural status of the barbarian, the nonperson, the Muslim, the monster, the terrorist” (Raza Kolb 124).