Our November LMCC meeting took place on Wednesday, November 29 at 5:45pm in UNC’s newly renovated HHIVE Lab (Greenlaw 524) and via Zoom. We discussed “The Pain Scale” by Eula Biss, originally published in Harper’s Magazine, 2005.

HHIVE Lab (Greenlaw 524) and via Zoom. We discussed “The Pain Scale” by Eula Biss, originally published in Harper’s Magazine, 2005.

If you missed the meeting, you can still access the text on the Readings page of this site!

You can also access the recording of our meeting here.

This was our final meeting of the semester. We will resume meeting in January of 2024. Right now, for Spring 2024, we tentatively plan to meet on the last Wednesday of each month (January, February, March, and April) at 5:30pm est in UNC’s HHIVE Lab, Greenlaw 524. If you can’t attend in person, you can attend in real-time via our usual Zoom link. We will send out an announcement during Winter Break with more information for our plans for the coming semester, especially regarding our January 2024 meeting.

A few reminders and announcements:

- Be sure to follow LMCC on Twitter and Instagram to show your support and receive regular updates!

- If you want to get more involved with LMCC, please send us other resources we should post to the site or suggestions for improvements, additions, future readings, etc. We’d love to hear your ideas and input! (See our email addresses on the Home page of this site.)

- Also, please feel free to spread the word about LMCC to other interested graduate or professional students at UNC.

Biss, Eula. “The Pain Scale.” Harper’s Magazine, 2005, https://harpers.org/archive/2005/06/the-pain-scale/.

Some key concepts:

History of the development of the pain scale:

- Emerged in the 1970s, institutionalized later when there was a push to take chronic pain more seriously (esp. pain not related to cancer)

- A desire to quantify pain to make it a “valid” biomarker (“pain as the fifth vital sign” movement)

- Mandated to take a pain score with a clinical visit

- Big Pharma jumps on this, taking advantage of the desire to take pain down to zero

- This also leads to patient self-satisfaction surveys

- Many unintended consequences (clinicians can be dismissive of people with pain ratings of 10 or assume a patient doesn’t understand the utility of the scale; complications in terms of race, gender, education, and socioeconomic status)

- Lichert scales (and quantitative data in general) can be problematic

- Opioids aiming for the elimination of pain rather than the management of pain

Other thoughts:

- Biss draws connections between the inability to quantify/express pain, alteration of states of matter (water boiling, water freezing), infinite and unknowable numbers, Dante’s Inferno, wind; Satan hanging upside down vs. a chicken being hung upside down, etc.

- Does pain exist if there’s no physical evidence of pain?

- Working on different definitions of what pain should be (vs. suffering)

- Misunderstanding between chronic and acute pain

- How do you define deviations from “the norm” when you’re in chronic pain?

- Consider not only pain’s intensity but also its duration

- Consider Alice James, sister to Henry and William

- Biss lays out the problem, but what’s the solution? New ways to express pain in a more individual, qualitative, subjective manner? Perhaps creating community (via social media and advocacy groups)

- Pain specialists won’t see/treat all people suffering from chronic pain (even when they believe that pain exists).

Some key passages:

“I am sitting in the exam room of a hospital entertaining the idea that absolutely no pain is not possible. Despite the commercials, I suspect that pain cannot be eliminated. And this may be the fallacy on which we have based all our calculations and all our excesses. All our sins are for zero” (5).

“Zero is not a number. Or at least, it does not behave like a number. It does not add, subtract, or multiply like other numbers. Zero is a number in the way that Christ was a man” (5).

“I’m sitting in a hospital trying to measure my pain on a scale from zero to ten. For this purpose, I need a zero. A scale of any sort needs fixed points” (5).

“The deepest circle of Dante’s Inferno does not burn. It is frozen. In his last glimpse of Hell, Dante looks back and sees Satan upside down through the ice” (6).

“There are zeroes beneath zeroes. Absolute zero is the temperature at which molecules and atoms are moving as slowly as possible. But even at absolute zero, their motion does not stop completely. Even the absolute is not absolute. This is comforting, but it does not give me faith in zero” (6).

“…grab a chicken by its feet and turn it upside down, and it just hangs there blinking in a waking trance. Zeroed. My mother and I hung the chickens like this on the barn door for their necks to be slit. I like to imagine that a chicken at zero feels no pain” (6).

“My father raised me to believe that most pain is minor. He was never impressed by my bleeding cuts or even my weeping sores. In retrospect, neither am I” (7).

“Every time I go to the doctor and every time I visit the physical therapist, I am asked to rate my pain on a scale from zero to ten. This practice of quantifying pain was introduced by the hospice movement in the 1970s, with the goal of providing better care for patients who did not respond to curative treatment” (7).

“There is a mathematical proof that zero equals one. Which, of course, it doesn’t” (8).

“The sensations of my own body may be the only subject on which I am qualified to claim expertise. Sad and terrible, then, how little I know…. I begin to lie to protect my reputation. I try to act certain” (9).

“Wind, like pain, is difficult to capture. The poor windsock is always striving, and always falling short” (10).

“Left alone in the exam room I stare at the pain scale, a simple number line complicated by only two phrases. Under zero: ‘no pain.’ Under ten: ‘the worst pain imaginable’” (11).

“The four vital signs used to determine the health of a patient are blood pressure, temperature, breath, and pulse. Recently, it has been suggested that pain be considered a fifth vital sign. But pain presents a unique problem in terms of measurement, and a unique cruelty in terms of suffering—it is entirely subjective” (12).

“Assigning a value to my own pain has never ceased to feel like a political act. I am a citizen of a country that ranks our comfort above any other concern. People suffer, I know, so that I may eat bananas in February. And then there is history . . . I struggle to consider my pain in proportion to the pain of a napalmed Vietnamese girl whose skin is slowly melting off as she walks naked in the sun. This exercise itself is painful” (12).

“…the reality that my nerves alone feel my pain is terrifying. I hate the knowledge that I am isolated in this skin—alone with my pain and my own fallibility” (12).

“Several studies have suggested that children using the Wong-Baker scale tend to conflate emotional pain and physical pain. A child who is not in physical pain but is very frightened of surgery, for example, might choose the crying face. One researcher observed that ‘hurting’ and ‘feeling’ seemed to be synonymous to some children. I myself am puzzled by the distinction. Both words are used to describe emotions as well as physical sensations, and pain is defined as a ‘sensory and emotional experience’” (13).

“There was nothing to illustrate my pain except a number, which I was told to choose from between zero and ten. My proof” (14).

“Overwhelmingly, patients tend to rate their pain as a five, unless they are in excruciating pain. At best, this renders the scale far less sensitive to gradations in pain. At worst, it renders the scale useless” (15).

“The distinction between test results that are normal or abnormal is often determined by how far the results deviate from the mean” (15).

“Despite my efforts to ignore it and to despise it, I am still susceptible to the mean—a magnet that pulls even flesh and bone. For some time I entertained the idea that my spine might have been straightened by my long-held misconception that normal spines were perfectly straight. Unknowingly, I may have been striving for a straight spine, and perhaps I had managed to disfigure my body by sitting too straight for too many years. ‘Unlikely,’ the doctor told me” (16).

“Infernal cartography was considered an important undertaking for the architects and mathematicians of the Renaissance, who based their calculations on the distances and proportions described by Dante. The exact depth and circumference of Hell inspired intense debates, despite the fact that all calculations, no matter how sophisticated, were based on a work of fiction” (17).

“…my nerves have short memories. My mind remembers crashing my bicycle as a teenager, but my body does not. I cannot seem to conjure the sensation of lost skin without actually losing skin. My nerves cannot, or will not, imagine past pain—this, I think, is for the best. Nerves simply register, they do not invent” (17).

“After a year of pain, I realized that I could no longer remember what it felt like not to be in pain. I was left anchorless. I tended to think of the time before the pain as easier and brighter, but I began to suspect myself of fantasy and nostalgia” (18).

“Although I cannot ask my body to remember feeling pain it does not feel, and I cannot ask it to remember not feeling pain it does feel, I have found that I can ask my body to imagine the pain it feels as something else. For example, with some effort I can imagine the sensation of pain as heat” (18).

“I would happily cut off a finger at this point, if I could trade the pain of that cut for the endless pain I have now” (19).

“When I cry from it, I cry over the idea of it lasting forever, not over the pain itself” (19).

“The pain scale measures only the intensity of pain, not the duration. This may be its greatest flaw. A measure of pain, I believe, requires at least two dimensions. The suffering of Hell is terrifying not because of any specific torture, but because it is eternal” (19).

“Euclid proved the number of primes to be infinite, but the infinity of primes is slightly smaller than the infinity of the rest of the numbers. It is here, exactly at this point, that my ability to comprehend begins to fail” (19).

“Experts do not know why some pain resolves and other pain becomes chronic. One theory is that the body begins to react to its own reaction, trapping itself in a cycle of its own pain response. This can go on indefinitely, twisting like the figure eight of infinity” (20).

“The problem of pain is that I cannot feel my father’s, and he cannot feel mine. This, I suppose, is also the essential mercy of pain” (20).

“But I am comforted, oddly, by the possibility that you cannot compare my pain to yours. And, for that reason, cannot prove it insignificant” (20).

“The medical definition of pain specifies the ‘presence or potential of tissue damage.’ Pain that does not signal tissue damage is not, technically, pain” (21).

“We have reason to believe in infinity, but everything we know ends” (21).

“Christianity is not mine. I do not know it and I cannot claim it. But I’ve seen the sacred heart ringed with thorns, the gaping wound in Christ’s side, the weeping virgin, the blood, the nails, the cross to bear . . . Pain is holy, I understand. Suffering is di-vine” (23).

“Through a failure of my imagination, or of myself, I have discovered that the pain I am in is always the worst pain imaginable” (24).

“‘One of the functions of the pain scale,’ my father explains, ‘is to protect doctors—to spare them some emotional pain. Hearing someone describe their pain as a ten is much easier than hearing them describe it as a hot poker driven through their eyeball into their brain’” (24).

“The description of hurricane force winds on the Beaufort scale is simply, ‘devastation occurs.’ Bringing us, of course, back to zero” (25).

– – –

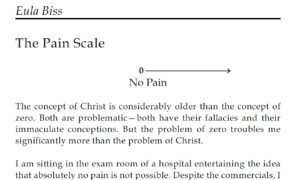

Note: The featured image for this post is a combination of two images from Biss p. 13, two variations on the Wong-Baker Faces scale.